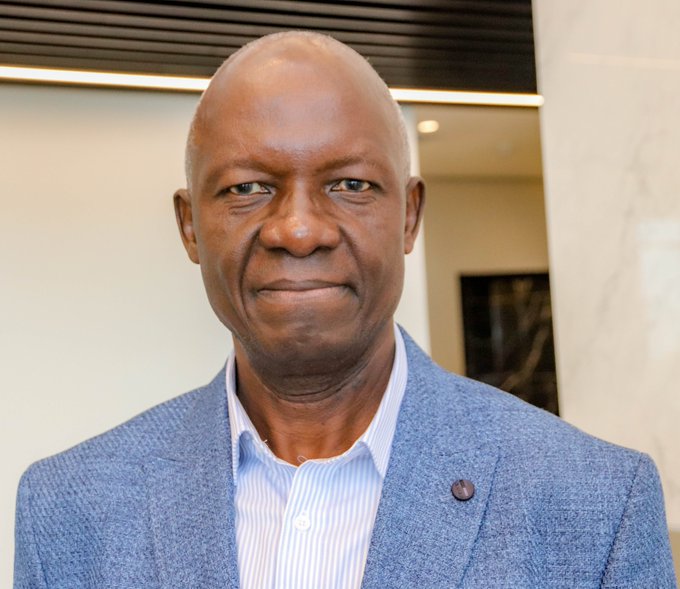

In this first part, an exclusive interview with ResearchFinds Editor-in-Chief Arinaitwe Rugyendo, Prof. Derek Peterson sheds light on Uganda’s ongoing efforts to reclaim 39 historical artifacts currently held in UK museums, including sacred Mayembe and human remains from Buganda. Prof. Peterson is a distinguished historian and Ali Mazrui professor of African Studies at the University of Michigan, specializing in East African history and the colonial legacy. His research focuses on African intellectual history and cultural heritage, and he has been a leading advocate for the restitution of African artifacts held in Western museums. In this interview, he delves into the complex bureaucratic and legal processes involved in securing the return of these cultural relics, which have been on a renewable three-year loan from the University of Cambridge. He discusses the broader historical significance of the artifacts, their acquisition during colonial times, and Uganda’s long-term plans to ensure their permanent return.

QN: What is so special about the Uganda Museum that has attracted your keen interest?

ANS: Its ethnographic gallery.

QN: Why?

ANS: Ethnographic galleries were part of the infrastructure of colonial rule. They made it seem as though Africans’ material culture, their identities, were essentially tribal. In this way, ethnographic galleries helped uphold the colonial indirect rule.

QN: What then is so special about the Ugandan one?

ANS: The most interesting thing about the ethnographic gallery at the National Museum has a fantastic history that should be uncovered. The core part of this museum reflects the presumptions of the 1950s and 1960s, which is basically that African history is frozen in time within the shape of ethnic containers. Any other form of political organizing—based on gender, labour, class, whatever—was thought to be foreign to African culture. African culture and identities had to be fixed. That’s the way the colonial government worked. Every African must belong to a tribal group. So the museum reflects the fallacies of indirect rule, the presumption that ethnicity is the only thing you need to know about African cultures. And that if you want to understand African identities, all you need to know is what tribes they are boxed into. That’s the way the colonialists thought about African politics. That’s why Uganda, like other British colonies, was segmented into these different tribal identities.

QN: What does this say about how we were framed by the colonialists?

ANS: The museum reflects the racist presumptions that guided British opinion about African cultures and histories. At the time of independence, they tried to break outside of this framework. The Hall of Science and Industry was opened right at the time of Ugandan independence, reflecting the interest in the Obote 1 government in demonstrating that industry, science, modernization, and development would come with self-government. But no one at the museum in the 1960s thought, ‘Let’s get rid of this ethnic politics that characterizes the museum. Let’s create our narrative about ourselves as a nation.’ Instead, the ethnographic gallery was kept in place, and it hasn’t been changed.

QN: What’s in this gallery that reflects these colonially structured ethnic representations of the country?

ANS: Everything in there is determined as if everyone belongs to an ethnic group. So if there’s a hut, it has to be linked to an ethnic community. If there’s an arrow, a spear, a piece of medicine, or some other object, everything is labeled as though it was essentially the property of the Bahima, Bakonjo, Baganda, Banyankore, or whatever. There’s nothing there about labor activism, nothing about women’s activism, nothing about the history of political parties, nothing about economic change. The whole presumption is that material culture can be segmented into different ethnic categories. Uganda has outgrown this museum. That’s my point.

QN: How has Uganda outgrown this museum?

ANS: There is a lot of will among the curators at the museum to find ways to tell interesting and exciting stories. However, the fabric of the museum has made it quite difficult to organize new narratives. The ethnographic gallery has survived the passage of time, partly because a lot of people find it interesting to learn about how their ancestors ostensibly lived. It’s all laid out; it’s well-labeled. It’s the most interesting part of the museum. It’s not that we want to get rid of the ethnographic gallery. Many students and Ugandans will remember going to the ethnographic gallery and looking at that wall full of arrows. Each arrow is labeled as though it belonged to a different ethnic group. For instance, there’s a Hima arrow, there’s a Nyoro arrow, and whatever. But in fact, those arrows were made into museum pieces because they were murder weapons. That is, many of them were seized by museum curators from the police stores because they had been introduced as evidence in a murder investigation. When the murder investigation had run its course, the arrows, the spears, and the bows would be handed to the museum, and then they would be incorporated into the exhibition. And when they became part of the exhibition, that history of acquisition was taken away, and they were treated as though they were relics of an ethnic community. But, there’s a traumatic story behind each of those objects, and it has to do with the history of political conquest and colonial governance.

QN: Should this museum transition the gallery to a nuanced categorization?

ANS: I strongly think that there should be a national history gallery in the National Museum of Uganda.

QN: And what should constitute it?

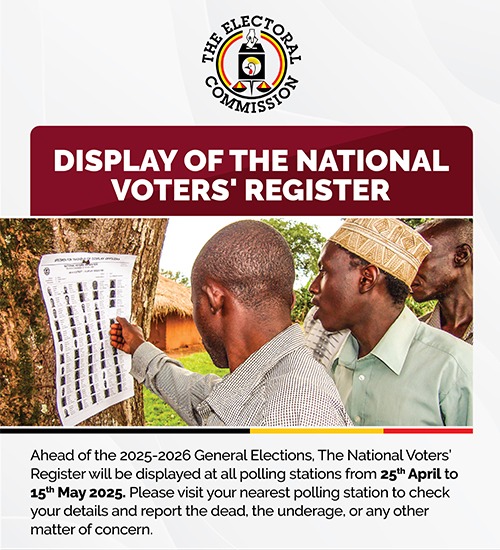

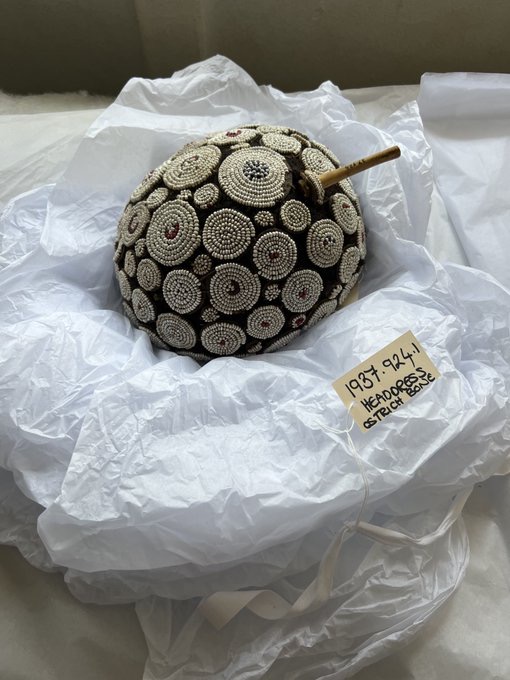

ANS: We’ve been working on that for the past seven years together. We had an exhibition in 2019-2020 drawn from the archives of the Uganda Broadcasting Corporation (UBC) to tell the story of the 1970s. We had another one in 2022, ‘Uganda @60’ was the name of the exhibition. That was more multimedia. There were some material objects, newspapers, archival material, and personal memorabilia, that were used to tell the story of how in 1962 Uganda became an independent state. And now, recently, the museum welcomed these 39 historical relics from Cambridge that came back from the Museum of Archeology and Anthropology. We are going to have an exhibition within the next year or two where those relics will be on show. That will be an opportunity to tell the story of how in the late 19th and 20th centuries, Uganda’s people, communities, and identities were made part of the British Empire. The story that each of these objects tells is a story about how in the early 20th Century, Ugandans, regardless of who they were, where they lived, what language they spoke, and what God they worshiped, were made into subjects of the British Crown in the early 20th Century. Their ways of life were devalued, their rituals, your rituals, and your gods were made into superstitions. The professions that people valued were made valueless, and that’s how in the early 20th Century, British collectors were able to acquire most of these objects. They had been devalued by dramatic political religious and cultural change at the dawn of colonial government. So, shrine priests, professional experts, and political authorities of kinds who were looking for new instruments of power, handed, sometimes sold, and sometimes voluntarily gave the instruments that were important to them off to curators like Rev John Roscoe, who took them to Cambridge. There were a few artifacts in the collection that have come back that were looted by thieves. But most of the objects that were taken to Cambridge were not looted. They were relics of the dramatic transformations in Uganda’s political life of the early 20th Century that were acquired by collectors because they had been devalued by the changes of the colonial government.

QN: Beyond devaluing the African systems of worship, what was the other hidden motive of the curators?

ANS: Why do colonialists collect the relics of their conquests? This is to do with demonstrating something about the culture and the identities of the people who they conquered.

QN: Something taking away their identity?

ANS: Partly it’s that. It’s also about something Ugandan media and social media commentators haven’t recognized.

QN: And what’s that?

ANS: It was often through the intermediation of people like Sir Apollo Kaggwa (in Buganda), Nuwa Mbaguta (in Ankole), Andrea Duhaga (in Bunyoro) that Rev. Roscoe acquired most of these things. Kaggwa was the key figure in the story. He was empowered as the chief regent of the Kingdom of Buganda, he was going around destroying shrines, stealing people’s land, and in the course of his efforts to build his power, he would often come into possession of important objects- Mayembe in particular- that were instrumental in the practice of power and…. He gave these things to Roscoe because he wanted to get them out of his kingdom. Because he wanted to centralize power in his hands. He presumed that everything rested on his fingers. Therefore, the fact that so many important things came to Cambridge; drums, Mayembe, and other instruments of power, reflects, how much power Kaggwa wielded. Roscoe was Kaggwa’s client. This is not to say Roscoe was self-interested. Roscoe was only effective as a collector because people like Kaggwa empowered him. So this is the story we want to tell.

QN: Through the exhibition of these relics?

ANS: Yes. The exhibition that we will put on will be about the re-making of Ankole, Bunyoro, Buganda, and other African societies in the early 20th Century, how Roscoe’s collection reflects the shifting, the sort of transformations of the way that political power worked in those years, the early 1900s.

QN: Are these Mayembe part of these 39 relics?

ANS: Yes. A number of those 39 objects are Mayembefrom Buganda.

QN: What has the research shown?

ANS: We are starting now. In the next year, we are going to start a period of research. This is going to involve four students from the History Department who we are bringing in to work with Museum Curators and with academicians from Makerere to create what we call ‘Object Biographies.’ That means for each of the object biographies, we are going to be researching what circumstances created the conditions for these things to be museumised.

QN: How are you going to scope this?

ANS: The students are going to be working in the National Archive in Wandegeya, Kampala City, going through all the files from the late 19th century to the 20th Century. They will be taking pictures of the objects to knowledgeable people to try and work out something about what these objects meant within a ritual and political context. We are going to find the relatives of the people from whom the objects were taken to work out something about the biographies of the people, and what happened. The interesting question we shall be asking is this: what happened to a professional healer when the instruments of his trade were taken away? Does that healer change his ground? What happens to his professional identity? That’s what are going to try to figure out. What can we know about the lives of people in the absence of these important objects that were taken away to Cambridge? What will follow will be an exhibition in 2025/2026 to showcase what we’ve learned

QN: There’s a burning question on social media about these relics. What happens to them after the exhibition?

ANS: We were supposed to have a press conference soon after they arrived in the country where were to lay all this out. We haven’t held the press conference again because His Excellency the President of Uganda was interested in welcoming these objects into Uganda in an official way. We haven’t therefore been able to explain all this and now the Cambridge curators have left the country.

QN: What do you have to say to Ugandans on social media who have been saying you are returning what was stolen?

ANS: It’s a very bureaucratic process to get a public institution like the University of Cambridge to give out objects like these to another country or other claimants. It would have taken us years and years and years to claim ownership of these objects for Ugandans. First of all, Ugandans should know there has been a Conservative government in power in Britain for the past 15 years. The Conservatives are not interested in emptying British Museums of things that were stolen from places like Uganda. There’s a law in place in Britain that makes it very difficult to formally transfer the title of Museum objects from a British institution to an African institution. What we’ve done is to bring these 39 objects here on a three-year renewable loan with the new Labour Government in place, Uganda Museum Curators will prepare to make a formal claim that the title of these objects should be transferred to Uganda. And it becomes a lot easier to make that claim bureaucratically when they are already here. We have to do the legal formalities, and that’s the next step. The social media people seem to think that this can somehow magically happen because they want it to happen immediately. But it takes time to make this happen. What we want is to assure everybody that that’s what we are going for. This is the first stage of a legal process that we expect will result in a change of title. In the meantime, having these objects here allows Uganda Museum curators to do the research that will allow us to properly showcase the circumstances in which they were collected and develop a stronger case for the legal transfer of title in a few years to come.

QN: You talk of a few years to come. Can you have an estimate?

ANS: If we had left them in Cambridge and tried to get the legal title organized, it would have taken years and years. Now that they are here, it becomes a lot easier. Some of them are human remains. Six are Balongo(Twins) which are the ritual twins of the Kingdom of Buganda. Right now we are working with the Kingdom of Buganda such that those Abalongo will be transferred from the Museum to the Kingdom’s custody as soon as the kingdom is ready to receive them. The government museum does not want to retain these objects within its possession. The other human remains will have to go back to wherever their proper custodians are within Buganda as soon as possible. Cambridge colleagues are quite clear in saying, that as soon as the kingdom works out its processes, they can claim those human remains and that will be very quick and easy to accomplish because they are human remains.

QN: What about the rest of the objects?

ANS: The other 31 objects consist of things that are not from human remains. Those will be treated separately legally and administratively. We expect within the period of the three-year loan, that the Uganda Museum will prepare a case, basically a claim on those 31 objects. They will allow the transfer of title to happen before the loan needs to be renewed. So, right now we are working with the museum in Cambridge on this research program. And it is good actually for the museum here in Kampala to have their input and professionalization and facilitation that the Cambridge people can provide because there are professional curators who can help colleagues here in Kampala learn how to care for these things.

COMING UP: In the second and last part of this interview to be uploaded on Monday next week, Dr Peterson reveals why over 6000 artifacts taken from Uganda are still held in the UK, what should be done about it, and the future of the Uganda Museum