By Dr. Gad Ruzaaza Ndaruhutse

The transformation of societies and economies globally owes a great deal to universities. The original institutions, such as the Universities of Bologna, Paris, Oxford, and Cambridge, emerged centuries ago to foster knowledge, scholarship, and leadership for societal advancement (Martin & Etzkowitz, 2000).

Over time, universities have taken on new roles, evolving from centers of knowledge to drivers of innovation and economic development, particularly in Europe, the Americas, and Australia.

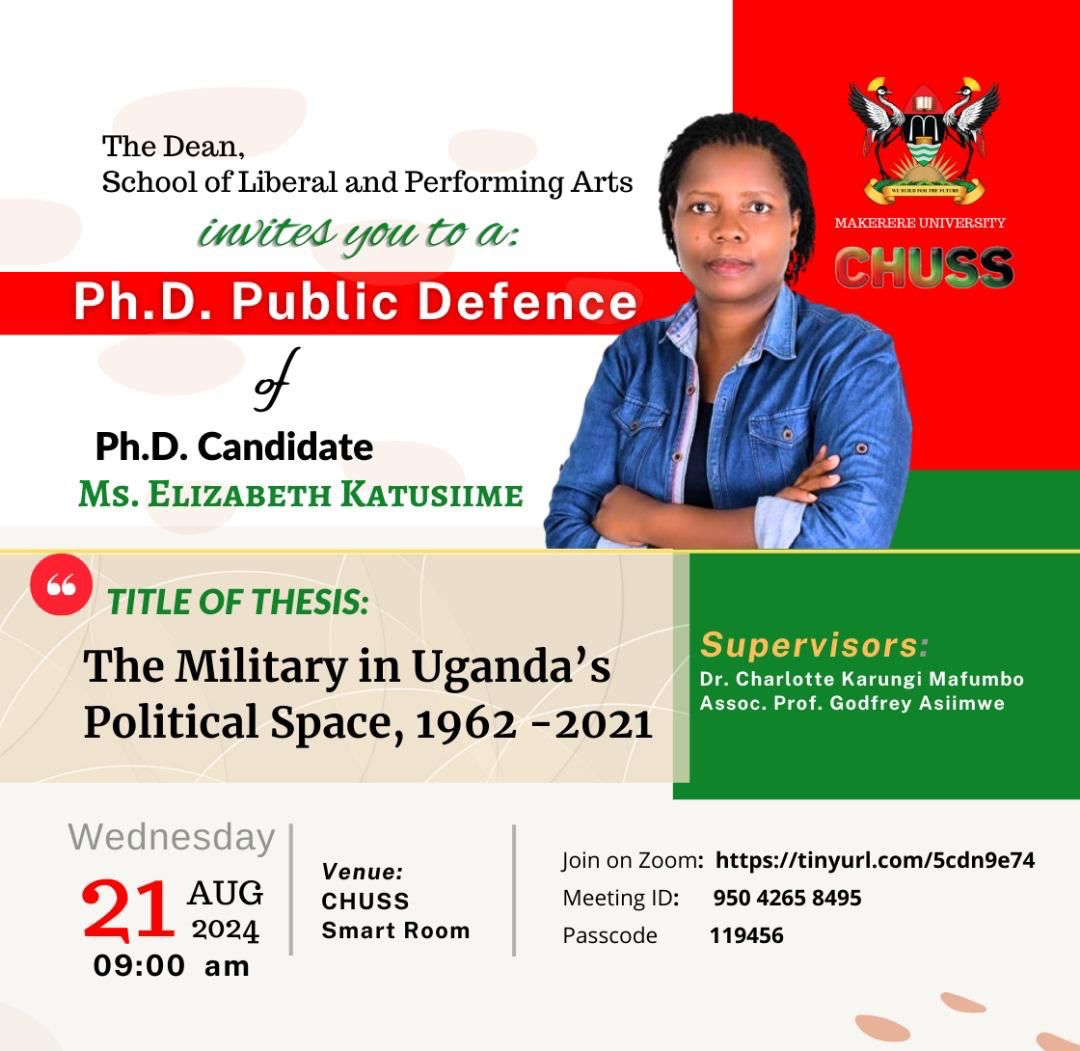

The most significant of these roles is producing new knowledge through doctoral education. In the knowledge economy, PhDs are central to research and innovation.

However, Africa’s contribution to the global knowledge economy remains meager—around 3% of global research output comes from the continent.

This stagnation can be traced to historical underinvestment in higher education and research. For decades, African universities operated under colonial-era systems that catered to the few elite, with little consideration for the needs of local societies. The question arises: what will it take for doctoral studies in Africa to flourish and enable the continent to harness its intellectual capital for societal transformation?

This op-ed reflects on the current state of doctoral education in Africa, the challenges facing both students and supervisors and possible strategies for improving PhD programs across the continent.

The Current State of Doctoral Education in Africa

Higher education in Africa has a long history, with institutions like the libraries of ancient Egypt and the universities of Timbuktu showcasing the continent’s academic roots. Yet, most modern African universities are modeled on colonial higher education systems, according to J.C Ssekwamwa. Following independence, many African countries established national universities as symbols of self-reliance. However, these universities primarily served small, elite segments of society.

In recent decades, there has been significant expansion in higher education, with private universities opening across Africa to meet the increasing demand for education. For example, Uganda’s higher education system has grown by over 700% since the early 1990s, with 45 registered universities, including seven public ones. Despite this expansion, doctoral education in Africa continues to lag far behind other regions, both in terms of output and quality.

The “massification” of higher education has led to many challenges, including issues of quality, funding, and alignment with job market needs. African universities face a critical shortage of PhD holders, leading to underfunded and understaffed research programs. As the demand for highly trained professionals grows, the continent must prioritize PhD education to remain competitive in the global economy.

Challenges Facing PhD Students in Africa

Pursuing a PhD is a demanding endeavor, but students in Africa face unique challenges that often hinder their success. One of the primary expectations of a PhD program is the production of new knowledge that can benefit society.

However, African PhD students often grapple with the disconnection between their research and the pressing social, economic, and political challenges facing their countries.

Many African universities have yet to fully appreciate the evolving role of higher education in addressing societal needs. This has led to a lack of curiosity-driven research, inadequate resources, and insufficient peer support. Additionally, the fear of loneliness, lack of confidence in writing, and challenges in proposal development create barriers to PhD completion.

The choice of a PhD mode—whether full-time, part-time, or professional doctorate—also plays a role in student success. Misconceptions about the difficulty of certain PhD tracks further complicate matters. Students often lack access to adequate funding, research infrastructure, and opportunities for professional development. Without clear guidelines and mentorship, many PhD students struggle to complete their studies on time.

Supervisory Challenges

Doctoral supervision is key to ensuring the quality of PhD research. However, in Africa, the shortage of qualified PhD supervisors exacerbates the difficulties facing students. Many supervisors are overwhelmed by competing priorities, lack adequate training, and rely on traditional, outdated methods of supervision.

In many cases, the relationship between PhD students and supervisors is strained due to a lack of communication and understanding. This is often compounded by an absence of peer support and collaboration between supervisors. A poor feedback culture and insufficient use of modern supervisory tools further complicate the situation. Additionally, the over-reliance on traditional face-to-face supervision methods, despite the availability of technological solutions such as video conferencing, limits the effectiveness of supervision.

Ethical Conduct of Research

Research ethics are another important consideration in doctoral education. Ensuring ethical conduct throughout the research process, from topic selection to data collection and publication, is critical to maintaining the credibility of research (Titus & Ballou, 2014). In Africa, however, financial constraints and resource limitations often lead to ethical dilemmas. For example, research participants may be coerced or unduly influenced by financial incentives, particularly in medical research involving vulnerable populations.

African universities must prioritize ethical training for PhD students and supervisors alike. This will help to avoid situations where research is compromised by unethical practices or financial inducements. Developing robust systems for ethical clearance and ensuring adherence to international ethical standards are essential steps toward building a strong research culture in Africa.

What Will It Take for Doctoral Education in Africa to Thrive?

To elevate doctoral education in Africa, universities must adopt new approaches that address the continent’s unique challenges. Several models have been proposed to enhance PhD programs and improve research output on the continent.

First, universities should invest in capacity building for supervisors. This includes training supervisors in modern supervisory techniques and encouraging collaboration between supervisors and students. Universities should also provide PhD students with access to research funding, conference participation, and mentorship programs.

Second, African universities must embrace technology to improve doctoral education. The use of digital tools for supervision, reference management, and communication can help mitigate the challenges of inadequate physical resources. Online platforms can also facilitate collaboration between PhD students and their peers across the continent and beyond.

Third, fostering a culture of responsible research is critical. This includes strengthening ethical standards and ensuring that PhD students understand the importance of ethical research practices. Universities should establish clear guidelines for ethical research and provide students with the necessary support to conduct responsible research.

Finally, African governments must prioritize funding for higher education and research. Investing in doctoral education is essential for building the continent’s intellectual capital and ensuring that Africa can contribute meaningfully to the global knowledge economy.

In conclusion, doctoral education in Africa holds immense potential to drive innovation and societal transformation. However, realizing this potential will require a concerted effort by universities, governments, and other stakeholders.

By investing in capacity building, embracing technology, and fostering a culture of responsible research, African universities can create an environment in which PhD students can thrive and contribute to solving the continent’s most pressing challenges.

Only through these efforts can Africa unlock its intellectual capital and take its rightful place in the global knowledge economy.

EDITOR’s NOTE: Dr. Gad Ruzaaza Nduruhutse is an academic, researcher, innovative thinker, and Practitioner carving out a niche in the Philosophy of Education, Primary Health Care, and Humanism at Mbarara University of Science and Technology, Uganda. He presented this paper at the monthly Network for Education and Multidisciplinary Research Africa (NEMRA) presentations series at Muteesa 1 Royal University on September 28.

Below are useful references he privileged for this article:

- Backhouse, J. P. (2009). Doctoral education in South Africa: Models, pedagogies and student experiences. Unpublished PhD thesis, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg.

- Badley, G. (2009). Publish and be doctor-rated: The PhD by published work. Quality Assurance in Education, 17(4), 331-342.

- Bastalich, W. (2017). Content and context in knowledge production: a critical review of doctoral supervision literature. Studies in Higher Education, 42(7), 1145-1157.

- Beaudry, C., & Mouton, J. (2018). The Next Generation of Scientists in Africa. African Minds.

- Bloom, D., Canning, D., & Chan, K. (2005). Higher education and economic development in Africa. Washington D.C.: The World Bank.

- Botha, J. and Mouton, J. 2019. “The execution phase: Responsible Conduct of Research (RCR) and ethics, literature review, project management and examination.” Course material of Module 6 of the DIES/CREST Training Course for Supervisors of Doctoral Candidates at African Universities. Stellenbosch University.

- Boughey, C & McKenna, S. 2019. “Roles and responsibilities of the supervisor and student”. Course material of Module 3 of the DIES/CREST Training Course for Supervisors of Doctoral Candidates at African Universities. Stellenbosch University.

- Castells, M. (2001). Universities as dynamic systems of contradictory functions. Challenges of Globalisation: South African Debates with Manuel Castells. Cape Town: Maskew Miller Longman, 206-223.

- Cloete, N., & Mouton, J. (2015). Doctoral education in South Africa. African Minds.

- Cloete, N., Bailey, T. & Maassen, P. (2011). Universities and Economic Development in Africa. Pact, academic core and coordination: Synthesis report. Cape Town: Centre for Higher Education Transformation

- Cyranoski, D., Gilbert, N., Ledford, H., Nayar, A., & Yahia, M. (2011). Education: the PhD factory. Nature news, 472(7343), 276-279.

- Delors, J. Amaji, I. Roberto, C. Chung, F. Geremec, B. et al (1996) Learning the treasure within, Report to UNESCO of International Commission on Education for the 21st Century, UNESCO Publishing

- Dugosh, K. L., Festinger, D. S., Croft, J. R., & Marlowe, D. B. (2010). Measuring coercion to participate in research within a doubly vulnerable population: Initial development of the coercion assessment scale. Journal of Empirical Research on Human Research Ethics, 5(1), 93-102.

- Gatfield, T. (2005). An investigation into PhD supervisory management styles: Development of a dynamic conceptual model and its managerial implications. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 27(3), 311-325.

- Herman, C. (2011). Expanding doctoral education in South Africa: Pipeline or pipedream? Higher Education Research & Development, 30(4), 505-517.

- Kasozi, A.B.K. (2003). University Education in Uganda, Challenges and Opportunities for Reform, Fountain Publishers, Kampala, Uganda

- Lajul W. (2011) Impact of African Traditional Ethics on Behaviour in Uganda, in MAWAZO: The Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, Makerere University, Vol. II No. 1 April 2011, (p.131) Makerere University Printery, Kampala

- Lee, A. (2018). How can we develop supervisors for the modern doctorate?. Studies in Higher Education, 43(5), 878-890.

- Martin, B., & Etzkowitz, H. (2000). The origin and evolution of the university species. Organisation of Mode, 2.

- Matas, C. P. (2012). Doctoral education and skills development: An international perspective. REDU: Revista de Docencia Universitaria, 10(2), 163.

- Materu, P. N. (2007). Higher education quality assurance in Sub-Saharan Africa: Status, challenges, opportunities, and promising practices. The World Bank.

- Maxwell, T. W., & Kupczyk‐Romanczuk, G. (2009). Producing the professional doctorate: The portfolio as a legitimate alternative to the dissertation. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 46(2), 135-145.

- McCulloch, A., & Thomas, L. (2013). Widening participation to doctoral education and research degrees: A research agenda for an emerging policy issue. Higher Education Research & Development, 32(2), 214-227.

- Mohamedbhai, G. (2014). Massification in higher education institutions in Africa: Causes, consequences and responses. International Journal of African Higher Education, 1(1).

- Mouton, J. (2011). Doctoral production in South Africa: Statistics, challenges and responses. Perspectives in Education, 29(1), 13-29.

- Ortega, S. T., & Kent, J. D. (2018). What is a PhD? Reverse-Engineering Our Degree Programs in the Age of Evidence-Based Change. Change: The Magazine of Higher Learning, 50(1), 30-36.

- Powell, S., & Green, H. (2007). The doctorate worldwide. McGraw-Hill Education (UK).

- Rodwell, J., & Neumann, R. (2009, January). Predicting timely doctoral completions: an institutional case study of 2000-2005 doctoral graduates. In AAIR 2007: Change, Evidence and Implementation: Improving higher education in uncertain times(pp. 1-10). Australasian Association for Institutional Research.

- Shabani, J., Okebukola, P., & Oyewole, O. (2014). Quality assurance in Africa: Towards a continental higher education and research space. International Journal of African Higher Education, 1(1).

- Ssekamwa, J.C. (1997) History and development of education in Uganda, Fountain Publishers, Kampala

- Teferra D. & Altbach, P.G. ( 2004). African higher education challenges for the 21st century, Higher Education 47: 21-50, Kluver Academic Publishers, Netherlands

- Tekeste Negash and Abiye Daniel, 2013 PhD Training in Eastern and Southern Africa: The Experience of OSSREA, OSSREA

- Titus, S. L., & Ballou, J. M. (2014). Ensuring PhD development of responsible conduct of research behaviors: Who’s responsible?. Science and Engineering Ethics, 20(1), 221-235.

- Varghese, N. V. (2004) Private Higher Education in Africa, IIEP, ADEA, AAU, UNESCO

- Venter, E. (2004) The notion of Ubuntu and communalism in African Educational discourse , Studies in Philosophy and Education 23: 149 – 160, 2004 Kluwer Academic Publishers, Netherlands

- Vilkinas, T. (2002). The PhD process: the supervisor as manager. Education+ Training, 44(3), 129-137.

- Waghid, Y. (2015). Are doctoral studies in South African higher education being put at risk?: leading article. South African Journal of Higher Education, 29(5), 1-7.

- Wandera, A. (1981). University and Community: Empowering Perceptions of the African University, Higher Education Vol 10, No. 3 (May 1981) pp 253 – 273

- Wellington, J. (2013). Searching for ‘doctorateness’. Studies in Higher Education, 38(10), 1490-1503.